French liberals and intellectuals turned eagerly to Jefferson to guide them toward a democratic form of government. As an ambassador at Versailles, he had a privileged view of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette and the corruption of their court. This led him to give his full support to the movements for reform – although he was as oblivious as any French aristocrat of the horrors that the Revolution was about to let loose. Jefferson was still in Paris when the Bastille fell on July 14, 1789, and the film resounds throughout with revolutionary rumblings and upheavals.

While deploring the poverty of the people, Jefferson appreciated all the riches of French culture and civilization. It was his first time abroad, and in a way, he was the prototype of the American in Paris, extending his knowledge of the liberal arts and the new sciences, and savoring the refinements of the mind and of the senses that France had to offer. And what he acquired he brought back to America: it was in France that he seriously pursued the study of architecture and began to plan the great buildings that he later designed for his own state of Virginia. He also brought back to Monticello, his plantation home, other French acquisitions – literally, for he departed from France with 86 packing cases containing books, furniture, paintings, statuary, scientific and musical instruments, wine, cheeses, clocks, and even fruit trees to plant on his hilltop, his "little mountain."

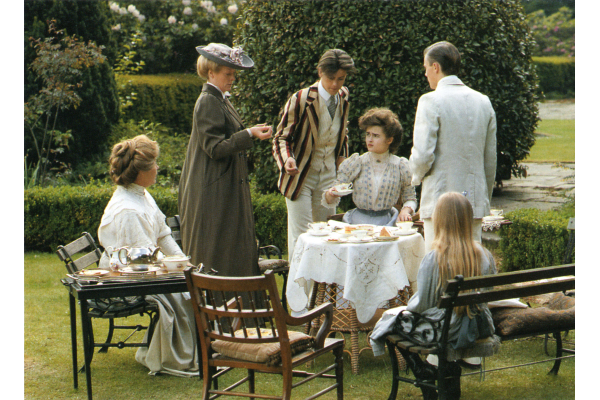

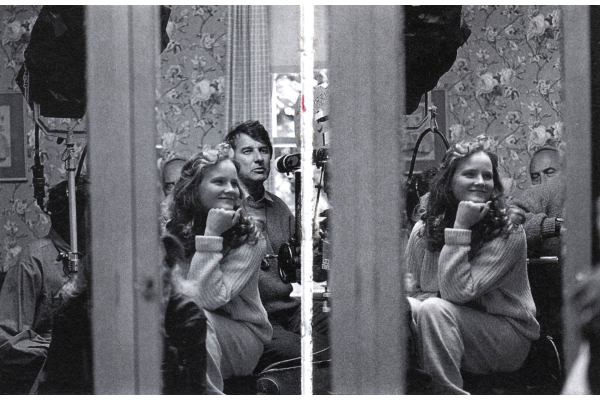

In his personal life, too, he was profoundly affected by these years in Paris. A lonely widower, he entered into a love affair with a beautiful Anglo-Italian painter and musician, Maria Cosway. This must have been his first experience of an attachment in the European manner, with a highly sophisticated European woman of advanced ideas about love and marriage. At first, Jefferson pursued her enthusiastically – he may even have considered himself head over heels in love. But while she was prepared to give up everything for his sake, to abandon her husband and her country, he drew back - or something held him back. For he had other attachments, which turned out to be stronger and deeper: to his wife, at whose deathbed he had vowed never to marry again; and to his two daughters, especially the elder, Patsy, with whom he had a relationship more passionate and clinging than is usual between father and daughter.

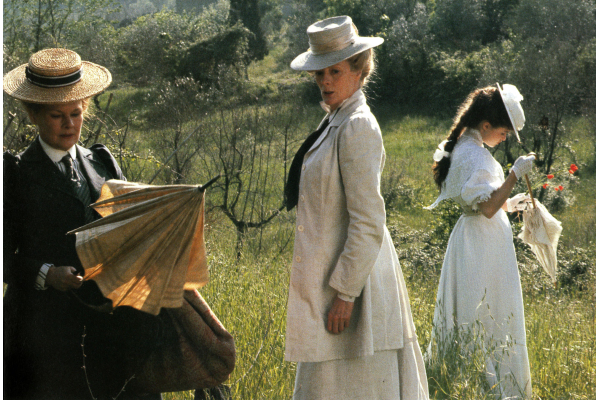

While he was still exchanging letters and romantic sentiments with Maria Cosway, he was forming yet another, simpler attachment. His younger daughter, Polly, arrived in Paris, accompanied by her nurse, Sally Hemings. Sally was the sister of James Hemings, who was already in Paris learning French cuisine to bring home to the Monticello kitchen. They were among the slaves whom Jefferson had inherited from his father-in-law - who, incidentally, had fathered them on one of his mulatto women. Sally was thus Jefferson's wife's half-sister, and while her resemblance to his dead wife may have contributed to her attraction to him, she was also a very pretty girl, who belonged to him. She must have carried deep echoes of his plantation home in Virginia - and, after several years abroad, Jefferson was getting to be very homesick. He longed for his beloved Monticello, and he wanted his daughters to be there, so that they could grow up as proper American girls, and not as what he considered frivolous Frenchwomen. When President Washington offered him the post of Secretary of State, Jefferson accepted and prepared to sail home with his family.

But part of his family - James and Sally - were not prepared to return home. James had learned to appreciate being a free man in Paris, and he persuaded Sally that they should stay there and not return home to American bondage, for in France slavery was illegal. It was only when Jefferson promised that he would give James his freedom, and to Sally too, and to all her future children – she was already pregnant with Jefferson's child - that they consented to go with him. Sally never claimed her freedom. She remained with Jefferson at Monticello for the rest of his life, bearing him six children, all born into slavery.

Jefferson in Paris shows Jefferson as the man of his time, a father of American Independence, an upholder of 18th-century ideals of liberty and equality, an American abroad deeply imbibing from the fountains of European culture; and a Virginian slave-owner who, besides giving his country her Declaration of Independence, also gave her more slave children, thus carrying on a tradition that he himself prophesied would "produce convulsions" through all the future generations.

Director’s Comments

There was, too, the wide-spread and well-documented custom in the slave states of such master/slave-woman liaisons, which were illegal in Virginia and elsewhere. Despite all this, Jefferson's modern biographers, with the exception of Fawn Brodie, continued to deny the story.

When Jefferson in Paris first appeared in 1995 it was condemned by American and British newspapers for supposedly playing fast and loose with the historical record. However, since then, proof of Jefferson's paternity of at least one of Heming's children has emerged from DNA studies and the story at last seems to have found widespread public and scholarly acceptance