Helen, Queen of the Nautch Girls

Shakespeare Wallah

Tony Buckingham (Geoffrey Kendal) and his wife Carla (Laura Lidell) are the actor-managers of a troupe of traveling Shakespearean actors in post-colonial India; they must grapple with a diminishing demand for their craft as the English theatre on the subcontinent is supplanted by the emerging genre of Indian film. Lizzie Buckingham (Felicity Kendal), the couple's daughter, falls in love with Sanju (Shashi Kapoor), a wealthy young Indian playboy who is also involved in a romance with the glamorous Bombay film star Manjula (Madhur Jaffrey). The Buckinghams, for whom acting is a profession, a lifestyle, and virtually a religion, must weigh their devotion to their craft against their concern over their daughter's future in a country which, it seems, no longer has a place for her.

Like its title, Shakespeare Wallah is a film of unexpected juxtapositions and cultural conflict; it is a look at changing values in art, and an examination of the question of what it means to be indigenous to a place. The nomadic lifestyle of the poor players -- artfully shown through many scenes of their fretful peregrinations around India -- provides the visual enactment of the problem of the Buckinghams' rootlessness, as here we find the first Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala exploration of that subject, the great dilemma for Merchant Ivory characters from Lizzie Buckingham to Ruth Wilcox inHowards End. "Everything is different when you belong to a place. When it's yours," Carla Buckingham quietly and regretfully tells her daughter, the young Englishwoman who was born in India and has never stepped foot on the soil of her "home" country.

Kendal and Lidell (whose experiences as head of a travelling company of players in India were the inspiration for the screenplay) provide a true and affecting center for the film, both onstage as Malvolio or Gertrude, and offstage as artists who have watched their audiences, their fortunes, and their prestige diminish by degrees. The young Felicity Kendal turns in a performance that would send her to stardom in England, while Shashi Kapoor displays a subtlety that suggests a maturation from his earlier work in The Householder.Madhur Jaffrey's inspired Manjula is to date one of the most memorable women in the Merchant Ivory filmography: her performance earned her the Best Actress prize at the 1965 Berlin Film Festival, where Shakespeare Wallah premiered. The musical score is provided by none less than Satyajit Ray, the Indian master-director and composer.

Ivory and Jhabvala's clever use of the Shakespearean scenes in the Buckingham Players' repertoire consistently illuminate and enrich the procceedings: a Maharaja in his darkened dining hall recites lines from the deposition scene in Richard II. Later on, Manjula condescends to visit the theatre and makes a rude, grand entrance while Tony, as Othello, soliloquizes before his murder of Desdemona. There is a deep irony in the juxtaposition of competing passion plays, on-stage and off (and Manjula's entrance in the middle of the scene is even more outrageous when we recall that Othello does not murder Desdemona until Act V of the play: Manjula has not only interrupted the proceedings. She has shown up only for the last ten minutes).

If the Shaksepearean texts cast light on the film, so the film also casts unexpected light on the Shakespearean texts it includes. Ivory and Merchant have captured on film perhaps the last moments in the last place in the world where itinerant players -- like those tragedians of Hamlet -- might arrive from the open road to play before a royal court. When the rain raineth in Feste's song at the end of Twelfth Night, the words acquire a new elegiac tone: the song becomes a summing up, not only for the play but for its players.

News

Mr. and Mrs. Bridge

Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward give "the performances of their careers" (Judith Crist) in Merchant Ivory's adaptation of Evan S. Connell's two novels Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge, artfully combined into one screenplay by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala.

Walter and India Bridge (Newman and Woodward) are a Midwestern American couple struggling to keep up with the changing world around them in 1930s America. Mr. Bridge, a stout-hearted, staunch paterfamilias, quietly lords over his children -- Ruth (Kyra Sedgwick), Carolyn (Margaret Welsh), and Douglas (Robert Sean Leonard) -- and his wife, who is warm and kind but lacks the independence to forge an identity apart from her husband. As the music, the mores, and the politics of Kansas City are transformed in front of them, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge attempt to keep up with the drama of a changing society within their own family: Ruth wants to go to New York and become an actress; Carolyn is determined to marry a man whom her father deems unsuitable; Douglas is embarrassed by his mother's attentions and rebukes her attempts at intimacy.

In one of the film's most memorable scenes, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge eat dinner at their country club while a tornado sweeps through Kansas City. The other patrons evacuate, yet Mr. Bridge insists on staying in the dining room until he finishes eating. As glass shatters and the world around is literally swept away, Mrs. Bridge searches for butter for her husband's dinner.

Blythe Danner and Gale Garnett play Grace Barron and Mabel Ong, two friends of Mrs. Bridge who seem to embody the comic ennui of suburban life, but play out a quiet tragedy underneath. Simon Callow is Dr. Alex Sauer, a worldly European psychiatrist who represents the progressive attitude Mr. Bridge scorns; Diane Kagan is Julia, Mr. Bridge's secretary, who stands unnoticed in the background until she steps forward to tell Mr. Bridge her secret.

"[A]nd we should die of that roar that lies on the other side of silence," George Eliot wrote in Middlemarch, one of the nineteenth century's great domestic dramas. Ivory and Jhabvala here seek out that roar that is underneath Connell's exploration of American domestic life: Newman's spartan silences and Woodward's abortive attempts to communicate with her husband and her children are perfect portraits of the things that are not said, and of the despair that lies beneath a quiet evening at home in the suburbs. The final scene, with Woodward at her best, provides us with one of the most affecting -- and terrifying -- images of Ivory's career to date.

Shot on location in Kansas City and in Paris (in this film, Merchant Ivory add the Louvre to their peerless list of shooting sites), the film was powerfully received at the box office and was greeted with rave reviews. The New York Times wrote that Newman and Woodward's roles were "the most adventurous and stringent of their careers." Woodward received an Oscar nod and the New York Society of Film Critics Award for her performance: her Mrs. Bridge is like an American Mrs. Dalloway, all warm smiles on her daily errands but seeped with a depth of feeling that her husband forever fails to understand.

The filmmakers were similarly lauded for a breakthrough in their first film with a Midwestern American theme: "With the quiet assurance of a perfect work of art," one critic wrote, "Mr. and Mrs. Bridge sweeps all other contenders off the screen to become the best movie of the year."

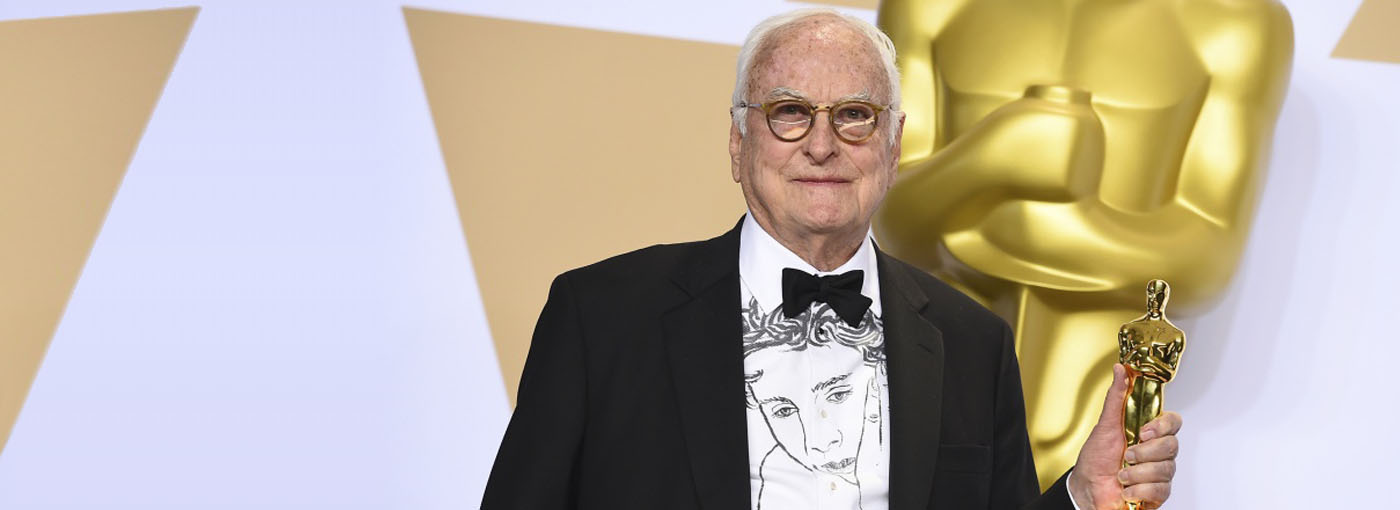

James Ivory Takes Home the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay

Social

Subscribe now and stay up to date

Stay up to date on new releases and re-releases of your favorites